On the symbolism and iconography of egg shapes (卵形の象徴と図像について)

On the symbolism and iconography of egg shapes, 1993

By Tadami Yamada

山田維史 (論文)「卵形の象徴と図像について」 日本語初出『AZ』1993年(新人物往来社)

As if to investigate anew what an egg, which hung before my eyes in a state that could be called a vision or a notion, was, my painting career, which I had just begun at that time, has taken on the appearance of an egg hunt ever since. In England, on Easter, children search for colorfully dyed eggs in the thickets of plants or among flowers in their gardens. Children who gather the most eggs receive a reward. My painting career is just like those children.

According to Jung, "The image of an egg depicts the outermost and the innermost, the greatest and the smallest, just like the idea of the Indian atman (self) embracing the world and living in the human heart as Thumb."

My interest is solely in the relationship between eggs and the "place" from which they appear. Is it a search for a place where the world that contains me and the world that I contain can hatch as one and the same thing?

Egg Hunt

In his theory of the collective unconscious, Jung mentions the egg symbol, citing several examples such as the Indian Prajapati (Figure 1). The egg symbol is probably one of the oldest symbols of humans. Here, I would like to take a look at what it is.

Roughly speaking, there are the following three types. However, they are often combined.

(1) Creation of the Universe

This is the myth of the cosmic egg, in which the heavens and the earth were created from an egg.

The Nihon Shoki records, "In ancient times, when the heavens and the earth (Ametuchi) had not yet been divided and the yin and yang (Meo) had not yet been separated, the chaos (Maloka) was like that of a chicken (Torinoko), cloudy and with fangs (Kizashi)." It is a well-established theory that this passage is a quote from the Sango Rekiki and other works.

The giant Pangu (盤古), who was born from an egg and separated the heavens and the earth, as recorded in the Sango Rekiki (三五歴記) and Goun Reki Nenki (五運暦年記), can be said to be a myth of the Han people.

Other myths include the myths of the Karen and Kachin peoples of Burma, the myths of the Rejag people of Sumatra, the Gajju Dayak people of Borneo, the Dogon people of Western Sudan, and the beautiful Finnish epic poem, the Kalevala.

Furthermore, Ashikaga Jun states that "in the belief of the ancient Iranians, the form of the material world has a structure similar to that of a bird's egg" (“Persian Religious Thought” ペルシア宗教思想).

According to Rosalie David's book "The Ancient Egyptians," in one of several creation myths from Hermopolis during the Old Kingdom, "instead of the concept of a primordial ocean, a cosmic egg appears as the origin of life." This egg was laid by a goose or an ibis, representing the great god Thoth, and inside the egg was the god Ra, who took the form of a bird that emerged to create the atmosphere or the world. Furthermore, in Thebes during the New Kingdom, "Amun, who incorporated the forms of all the earlier creator gods into himself, was born in secret from the egg of the primordial hill, from which all the other gods and the entire universe arose" (translated by Kondo Jiro).

Also, according to the legend of Orphicism, which flourished during the early Christian period, the Great Mother Goddess and the snake-like god Ophion mated and laid an egg from which the sun god Apollo was born.

As I wrote at the beginning, Japan has a creation myth that is explained by eggs. In the section on Emperor Nintoku in the second volume of the Kojiki (古事記), there is a legend that seeing wild geese lay eggs, which are not supposed to be born in the land of Wa, is seen as an auspicious event. However, when we look at the shape of the egg, it seems that it has not been sublimated into a symbol of the collective unconscious of the Japanese people.

Orikuchi Shinobu says, "When the ball of the soul takes shape, it appears in various forms, and the one that appears in the best form among these was thought to be a ball. The symbol of the abstract ball (soul) was none other than the concrete ball" (“The Sword and the Ball” 剣と玉).

The ball is, so to speak, a container for the soul, and it seems that spirits reside in a piece of cut log (woodcutters call this a ball), a stone, a shell, a cocoon, and an egg.

There is no difference between a sphere and an egg shape.

In Volume 3 of Kiuchi Sekitei's Unkonshi (雲根志), in the section on statues and figures, there is a description of a rare stone called "Stone Egg." It appears to be an ordinary stone, but when you break it open you will find a reddish egg-shaped stone the size of a hen's egg inside. This is Stone Egg. Judging from its color, Sekitei writes that it is probably made of iron. It is not difficult to imagine that such a rare stone would have become an object of worship.

The Tamaishi Dosojin in Yamanashi Prefecture and the Koshin-sama statues found in parts of Saitama and Tochigi Prefectures have spherical natural stones as their deity objects.

The Okoyasu-sama statue at Mitsuzuka in Nozawa Town, Minamisaku District, Nagano Prefecture also has a round pebble as its deity object, and pregnant women place this pebble under their futons to pray for a safe delivery.

The Maruishi god in Yamanashi Prefecture's Konan Town is a truly beautiful, perfect sphere.

Nakazawa Atsushi has conducted many years of research into the Maruishi gods throughout Yamanashi. According to this, Maruishigami are natural stones that are almost perfectly round, but some are irregular and egg-shaped. However, the concept of an egg shape is not found anywhere.

In this respect, it is completely different from the stone egg god enshrined at Gujibong Peak in Gimhae, at the southern tip of the Korean Peninsula, in connection with the myth of King Kim Suro's descent to earth.

There are countless examples of spheres and circles, from the sphere depicted in Kano Hogai's "Kannon of the Sorrowful Mother" (1888) to the circle of Zen. Despite Orikuchi's theory, it seems that there is something to be said about the Japanese aesthetic sense here.

Here, I would like to introduce the only example of an egg shape created with intention and that is of historical interest, as far as I know, in Japan.

It is a gold and silver egg-shaped container with double honeysuckle arabesque pattern openwork that is placed in the central corner of the five-story pagoda of Horyuji Temple.

This egg-shaped vessel is a relic container, but it is probably of an unusual design (Figure 2).

(Figure 1) (Figure 2)

Shapes of sarira containers that have been passed down in Japan include pagoda-shaped, nested box-shaped, jar-shaped, and pot-shaped.

The stupa-shaped items found in Gandhara from the 3rd to 7th centuries are probably the original shape of sarira containers. After the Buddha's Nirvana, his cremated remains were divided into eight parts, and the kings of eight countries built stupas to house them. King Ashoka, the third Mauryan dynasty, removed the sarira from seven of these stupas and built 84,000 stupas to house them. The number 84,000 probably means many, but the stupas built by King Ashoka are said to have been made of earth, with wooden fences and masts. After the king's death, Buddhism lost its patron and declined, and in this atmosphere, the stupas were rebuilt out of stone. Whether it is an item excavated in Gandhara or one handed down to Japan, small reliquary containers can be traced back to large stupas.

Egg-shaped reliquary containers are unusual in design, and although the idea of an egg as a symbol is not related to primitive Buddhism, over time it has come to adorn Buddhism.

There is something called Rantō (an egg tower), which is commonly seen in esoteric Buddhist temples. It consists of a stone pillar called a pole on a square or octagonal base, a central base and a seat called a lotus petal shaped base, and an egg-shaped tower body on top. The character for this is sometimes written as orchid tower*. This character is often seen in Edo literature and Kabuki, and orchid tower place primarily means graveyard. However, originally it was probably an egg tower. This is because the egg-shaped tower body is called "anda" in Sanskrit, which means egg.

The egg tower is probably an evolved form of the stupa. Primitive Buddhism is a practical religion (a religion whose main purpose is for believers to practice asceticism and to practice actions based on its doctrine in everyday society) and does not contain any elements of idolatry. However, as it spread, the Hindu concept of Brahmanda (the cosmic egg) was introduced, and via Gandhara it was assimilated with Tibetan Bon religion and linked with yin-yang and the five elements, resulting in the mandala.

Jung points out that "the square plan of stupas can be seen in most Lamaist mandalas."

The foundation of the stupa is thought to have originated in Gandhara. The lotus throne, or the offering on the egg tower, also first appears in the Gandhara Buddha. I believe that the egg tower is a type of three-dimensional mandala. The egg contains the Buddha's relics and is at the center of the world.

The egg tower is, so to speak, a symbol of the egg, which appears and disappears. And so, the egg-shaped relic container from the Five-Story Pagoda of Horyuji Temple appeared before us like a stroke of luck.

*note: The kanji characters “卵 (egg)” and “蘭 (orchid)” are pronounced the same way, "ran."

(2) Myths of the Founder of the Egg-Born People

This pattern tells of the egg-born birth of the founder of a nation, a king, a hero, or a person with special abilities.

The story of the origin of King Hyeoggeose, the founder of Sinla, is a typical example of the myths of the founder of the egg-born people.

According to the "Sangoku Shiki," "Prince Sobeol, head of Koho village, was looking at the foot of Mt. Yangsan when he heard a horse kneeling and neighing in the woods near Najeong. He went to look at it, but suddenly he could not see the horse. There was only a large egg, which he dissected and a baby came out of. (Omitted) He was honored by the gods of his birth, and was made king." Hyeoggeose means "bright world" (Figure 3).

Regarding Korean and southern ancestral egg-laying myths, Mishina Akihide has conducted valuable research, collecting 35 examples and introducing all of them.

Although Mishina does not mention them, the Soushinki (捜神記) contains a story about a boy named Ketsu who was born from a giant egg during the reign of Emperor Kai of the Jin dynasty, and who led Liu Yuan to complete the construction of his fortress when he was just four years old.

The Miao people of China also have an egg-laying myth. It is said that their ancestor, Hudayemama (also known as Meipang Meiliu), who is the progenitor and originator of all things, was born from a giant maple tree after the creation of the world, but eventually married water bubbles and laid 12 eggs, from one of which mankind was born.

Pariacaca, a hero of the Incas of Peru, was also born from one of five eggs that suddenly appeared on the top of a mountain.

There is another egg myth in Peru. The sun dropped three eggs made of gold, silver and bronze on the people of Cusco. Eventually humans were born from each of these eggs. From the golden egg came a brave man, from the silver egg came a noble man, and from the bronze egg came a humble man. These people became kings, priests and slaves, and so a hierarchy was created among the Peruvians.

The dwarf chief who appears in the legends of the Maya people of Mexico is said to have hatched from an egg that was the result of a marriage between an old woman sitting under a large tree on the bank of an underground river and a snake that she kept nearby, which fed on human babies. The dwarf was a weak and crybaby, but when encouraged by his aged mother he displayed great strength, eventually smashing the king's head with a bundle of hard wood called cogoyol and becoming chief. Many ethnic groups believe that a spirit resides in the head and consider it sacred. Some ethnic groups also believe that a succession of kings is achieved by assassinating the king.

(Figure 3) A fossilized egg was one of the grave goods excavated

from the Cheonmachong Tomb of Silla.

Collection of the Gyeongju National Museum

(3) Iconography of doctrines and ideas

[Leda and the Swan]

The Greek myth of Leda and the Swan (Zeus) can be seen as a type related to the creation of the universe, but here we emphasize the element of the emergence of a dualistic conflict of human destiny and emotions.

This myth must have really stimulated the imagination of artists, as many works have been created based on it. As can be seen from the illustration shown, the number of eggs depicted in each work is different. This is because there are various theories about the father of Leda's children. In any case, Leda's children born from eggs, Castor and Pollux, embody "harmony," while Helen and Clytemnestra embody "disharmony." Iconographically, the egg must split into two hemispheres, and each twin must have half of the shell attached.

This worldview of moving from a primordial monistic state to a dualistic conflict is reflected in Plato's idea of the androgynous Demiurge. In other words, the human form is spherical in its perfect form, and since its nature was cut in two, each half yearns for its own half and tries to be united. We are each a tally of humanity, and therefore each is constantly searching for his own tally (“Symposium”).

This idea was carried over into Platonist philosophy during the Renaissance, and inspired Leonardo da Vinci to take up his brush.

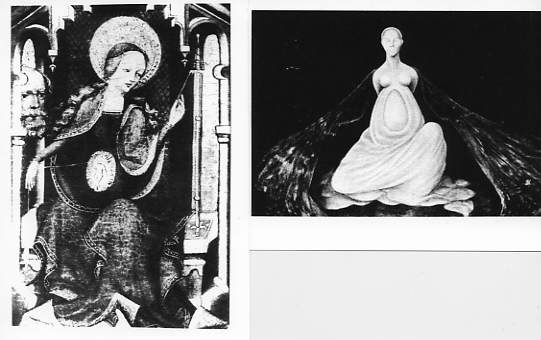

There are only a few "Leda and the Swan" paintings that are said to be his original (Figure 4), but the original can be inferred from works that are thought to be in the da Vinci school (Figure 5).

What is interesting about Leonardo's drawing is the presence of a cattail behind the two eggs. In Christianity, cattails are unclear in their biblical interpretation, but in art they are symbols of "rebirth" and "salvation." Other artists focus on the eroticism of intercourse or the rarity of the body as a form of beauty (Fig. 6), and the eggs are merely an accessory, but the presence of the cattail makes it clear that Leonardo was clearly paying attention to the presence of Leda's children.

(Fig. 6) (Fig. 7)

[The Virgin Womb]

What is unusual about Buffet's Leda is that it depicts an ostrich instead of a swan, and that it depicts three eggs that do not fit any of the theories about the egg-laying of Leda's children (Fig. 7).

In medieval Christian doctrine, ostrich eggs are a symbol of the virgin birth. They are also a symbol of rebirth, as they hatch even in the hot sand of the desert. Considering this, Buffet may have been expressing the sacred conception of Mary, who has the appearance of the Leda myth.

In Piero della Francesca's 15th century "Montefeltro Altarpiece," an ostrich egg hangs from a shell-shaped canopy on a single thread above the head of the Virgin Mary, who is praying with the infant Christ on her lap (Fig. 8).

In this painting, the shell is also a symbol of spiritual rebirth. Christianity inherited this symbol from Egypt and Rome. It goes without saying that it is a symbol of the vagina (see Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus").

Dali referenced this altarpiece when he painted "Madonna of Portlligat" (Figure 9).

(Fig. 8) (Fig. 9)

Looking at the history of depictions of the Virgin Mary's conception, there may not have been many simple, direct depictions of the womb.

Jung also gives the example of "Christ in the Womb of the Virgin Mariano" (c. 1400) by a painter from the Upper Rhine (Fig. 10).

However, although not a womb view, egg-shaped conception images appear, as if by atavism, in the works of Leonor Finney (Fig. 11), Wanderlich (Fig. 12), and Dali (Fig. 13).

(Fig. 12) (Fig. 13)

[Resurrection and rebirth]

Painting eggs is a well-known Easter custom.

In Ukrainian legend, when Jesus was crucified, the Virgin Mary offered an egg to beg for his life, and her tears of sorrow fell onto the egg. It is said that decorating Easter eggs with polka dots represents the tears Mary shed at that time.

It is a custom that is widely practiced in the Western world with many legends, but it can also be seen in ancient China, Egypt, Persia, and Greece.

In the Celtic Druid festival of spring, eggs are dyed red in worship of the sun. Winter dies, and with the blessing of the warm sun, a new season of budding arrives.

In the Keisosaijiki (“Jingchu Almanac” 荊楚歳時記) , among the foods and drinks to be eaten on the first day of the New Year, it says, "Each person should eat one chicken egg." Regarding this custom, Li Xianzhang, in his book Toso Shuzoku Kō (屠蘇習俗考), explains that "the baby organism that has just begun to develop from an egg, that is, an embryo, is called 'Xing,' and each of them prays for smooth development and growth into a solid substance, following the formation of the embryo." Eggs are offered to the gods as an important symbol of resurrection, regeneration, and fertility, and appear among the foods at banquets.

[Etruscan Funerals]

The "Etruscan Civilization Exhibition," which toured four cities in Japan from 1990 to 1991, was the first full-scale exhibition outside of Italy to introduce Etruscan civilization.

Many people may remember the ceramic brazier containing three broken eggs, which was excavated from the Panditaccia cemetery in Cerveteri (Fig. 14). There is no doubt that the eggshells were used for banquet food. But why eggs?

I believe that Etruscan funerals were influenced by Orphicism, and that eggs were offered to the chief god Phanes (Dionysus of Thebes) as a symbol of rebirth and sexuality.

Despite the existence of a huge amount of excavated material and external historical materials, it seems that it is difficult to know what the Etruscan civilization was really like because all of the Etruscan writing written by the Etruscans has been lost.

Etruscan religion appears to have been complex and had strict rules, but was heavily influenced by the Pythagorean religion of Orpheus, and also incorporated mysteries related to the worship of Dionysus. Orpheus is the greatest muse in Greek mythology, but he is also said to have been a follower of the god Dionysus. Jung states of Orphic Phanes, "It also means Priapus, and is androgynous and is identified with Defionysus Lysius of Thebes."

According to Euripides, Dionysus "was conceived by his mother and given birth amid a flash of lightning, but was struck by lightning and died. Zeus, the son of Cronus, immediately cut open his own thigh and placed the child in his new womb, hiding it from Hera's eyes with a golden clasp. When the month was full, the living god was born, and his father placed him in a wreath and put a rudder around his head" (Bacchus, translated by Matsudaira Chiaki).

Also, Kure Shigeichi says, "In essence, he must be the spirit of plants. He is a seed hidden in the earth, which is brought to life by merciful rain, and eventually grows, flourishes, and bears fruit. Then, when the time comes, he must eventually wither and die again. Prayers for his death and rebirth are the focus of Dionysus's rituals." The followers of Dionysus carried a staff, wore deerskin clothing, and had ivy or grape leaves in their hair. Dionysus was also known as Bacchus, the god of the grape press.

Evidence of the close relationship between eggs and the worship of Dionysus can also be seen in the egg offerings housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Please take a look at the photo I took (Figure 15). A large terracotta egg is placed inside the urn. A strange painting of a red face with a string-like object on its head decorates the front of the urn. Might the owner of the red face be identified with Dionysus? The twisted wisteria handles also indicate this.

And from ruins such as Veio in Etruscanism, statues of a man (Silenus) and a woman (Maenad) worshipping Dionysus have been excavated as roof decorations for temples.

The bronze "female donor" statue exhibited in the above-mentioned exhibition holds an egg in its right hand and a pomegranate in its left hand (Figure 16). This statue was excavated from a sanctuary dedicated to the underworld goddesses Uni (Juno) and Wei (Demeter), who are in charge of fertility and rebirth. Eggs are also symbols of fertility and rebirth here, while pomegranates are associated with the underworld and are a symbol of fertility. The name of Dionysus does not appear to be found in this sanctuary. However, pomegranates are related to Dionysus.

According to Greek mythology, a fairy who was told by a fortune teller that "you will wear a crown" was transformed into a pomegranate by Bacchus, who then placed the crown on the top of the fruit. We have already mentioned that Bacchus is another name for Dionysus. Another theory says that pomegranates were born from the blood of Dionysus.

"Phanes in an Egg" (Figure 17), an Orphic ritual statue housed at the Modena Museum in Italy, which Jung also used as a reference illustration, is, as its name suggests, about to emerge from an egg.

In "The Bacchanalia," Euripides has Pentheus say that Dionysus "gave divination to birds and examined their entrails." This is a reference to Dionysus, not to Etruscan rituals. However, the fact that Etruscan tomb ruins are filled with eggs is evidence of such activities.

Of course, making a direct connection between the Greek world and Etruscans is merely a continuation of the historical prejudice against Etruscan civilization. Nevertheless, under the influence of Orphicism, eggs were enshrined there as a symbol of rebirth and resurrection, and were eaten as a funerary food for prayer.

(Fig. 14) (Fig. 16)

(Fig. 15) (Fig. 17)

[The Fall of the World]

When we look into the iconography of eggs, we find that the commercial-style cliche of fresh eggs does not necessarily apply. Many eggs incorporate negative images, so to speak, to highlight the fall of the world.

The eggs that appear in Bosch's works are one such example (Fig. 18).

The performers inside the eggs are hypocrites, frivolous reformers, powerful theologians, and unjust inquisitors. ...the world is completely corrupt.

Bosch is said to have belonged to the Adamites, a "cult of the free spirit." Although there seems to be no definitive proof, his paintings may be pictorial interpretations of those teachings.

The 20th century artist Escher treated the egg as an image of chaos (Fig. 19).

The geometric form in the center represents order, while the scattered objects represent disorder. We see that in his mind there is no image of a mythical egg at all. His egg has cracked, and only the empty shell exists in the world as rubbish that produces nothing.

In André Breton's photomontage titled "The Egg of the Church," there is no image of an egg to be seen anywhere on the screen (Fig. 20).

In the far center, there is a face wearing a priest's hat, and in front of it, a woman is half-lying, flaunting a provocative pose, as if offering. She is leaning on the priest's scepter.

What is the origin of this title?

It was Saint Methodius of the 4th century who said, "A virgin with a pure soul can be betrothed to Christ," but what supports this statement is the belief that women embody vice through the temptation of lust, and are close to the devil, as tools of denial of the faith. At the Council, women were called the "poison of the scorpion" and the "evil sex," and were subjected to cruel torture. In other words, to the Church, women were "witches' eggs."

Breton wrote LE SERPENT (the snake) in the subtitle. The serpent is the tempter in the Garden of Eden, and this French word (spelled the same in English) is also synonymous with the devil. In this work, he shows that eroticism is guaranteed by an intimate relationship between prohibition and violation.

(Fig. 18)

(Fig. 19) (Fig. 20)

[Alchemy, the Womb, the House]

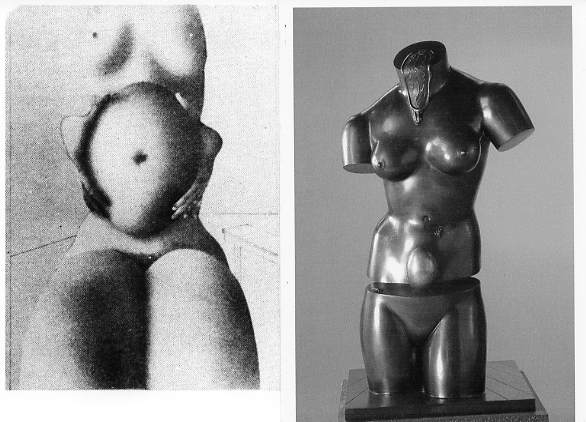

From the Middle Ages to the 16th century, European art, whether literature or fine art, cannot be discussed without the influence of alchemical thought. In alchemical philosophy, the universe is believed to be a harmony of masculine and feminine within itself, and the hermaphroditus (Hermaphroditus) is considered the ultimate ideal. This idea crystallizes in the image of an egg as a more general symbol, and therefore also as a mysterious symbol (Fig. 21).

In Psychology and Alchemy, Jung states, "In alchemy, the egg represents the chaos perceived by the alchemist, the prima materia, in which the soul of the universe is imprisoned in chains. The egg is symbolized by a round cooking pot, from which emerges an eagle or phoenix. This eagle or phoenix is the now liberated soul, which ultimately corresponds once again to the Anthropos that was once imprisoned in nature."

The illustration shows an artificial dwarf, symbolizing mercury, growing in a retort called the "philosopher's egg," born from a "chemical marriage" (Fig. 22).

Jung explained that "the container (retort or melting furnace; Yamada's note) is a kind of matrix or uterus (both meaning "womb") from which the 'son of philosophy', that is, the miraculous stone (labis), is born. For this reason it is said that the container must be egg-shaped and not just spherical."

An almost identical image of this egg retort appears in science fiction illustrations of the 1920s (fig. 23).

If we are to look for differences between this work and alchemical thought, it is that the joys and anxieties of faith in machines crossed the artist's mind. The will to ascend toward universal self-completion seen in alchemy may no longer be found in 20th century thought.

(Fig. 21) (Fig. 22)

(Fig. 23)

The Hermaphrodite will to self-completion can instantly turn into narcissism if one shifts the antenna of one's perception of the world even slightly. This was even easier in the self-confessional trend of modern art, especially 20th century art. The egg becomes a container for narcissism.

Dali's egg

In 1938, he visited Freud with "Metamorphosis of Narcissus" (Fig. 24), which he had completed the previous year. He apparently explained to the doctor that this work depicted "death and fossilization."

There is also a photograph of him in a fetal position, naked inside a plastic egg (Fig. 25). If one were to realize Dali's desire to return to the womb at the level of everyday life, the only option would be to make an egg his residence. In fact, Dali decorated his house in Figueres with giant eggs and was apparently fond of egg-shaped rooms.

(Fig. 24) (Fig. 25)

In 1978, architect A. Briere published a book called "The Egg" in which he presented plans for an egg-shaped skyscraper (Fig. 26). However, it was never realized.

Why has this egg-shaped house, which should be the most peaceful and happy, never appeared in architectural history, or even in prehistoric legends? It seems strange given the variety of images of the egg shape. Perhaps purely technical issues quickly suppressed the image. On the other hand, many plans for spherical architecture remain as fantasy drawings, and in 1967, Buckminster Fuller, the creator of the Dymaxion theory, even announced a "floating geodesic sphere" with a diameter of more than 1.5 miles.

Mircia Eliade states that there are two important propositions in the symbolism of the holy city (the center of the world), the doctrine of divination that governs the base of the city, and the idea that justifies the rituals associated with city construction, and he says the following:

"1. Every construction repeats the great cosmic work, the creation of the world.

2. Therefore, whatever is built has its foundation in the center of the world (for the creation itself, as we know, arose from the center)." (The Myth of Eternal Return)

Despite this, the image of the egg never appeared in earthly architecture, either as a sanctuary that retained its mythical prototype, or as a womb-like place of rest. The absence of egg houses is nothing short of mysterious.

For some reason, all civilizations around the world have refused to endow architecture with sensuality. The floors and walls of our dwellings do not flexibly embrace the body like a womb.

(Fig. 26)

Finally, I would like to mention the Neolithic house of Riedental near Cologne, introduced by Bernard Rudolfsky, as the most egg-like dwelling. No, it is not egg-shaped. It is a sensual dwelling, as if the inside of a womb were like this. It is an absolutely amazing dwelling with no parallels anywhere in the world.

It is a "curved complex structure" that is unconventional by any standard, with irregular planes that are by no means accidental, undulating walls, and shell-shaped depressions scattered all over the interior, expressing the joy of free-spirited form.

It seems that "these depressions invite people to lean back in them and, as it were, sneak into the earth, into the earth with a highly refined shape."

This is indeed an invisible egg-shaped house that evokes the dream of a womb.

©Tadami Yamada. All Rights Reserved.

コメント

コメントを投稿