About C.G. Jung's Landscape Paintings

About Jung's Landscape Paintings

by Tadami Yamada

「C. G. ユングの風景がをめぐって」1993年 山田維史

Psychologist Jung attended lectures by Pierre Janet in Paris from 1901 to 1902. During that time, he painted two landscapes.

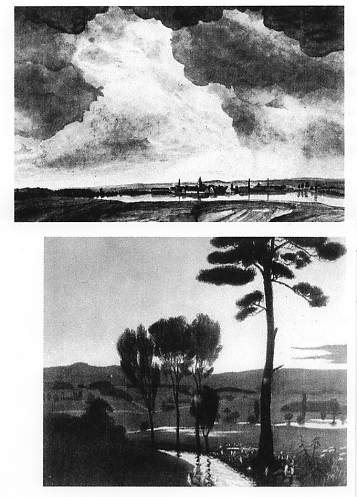

The work, dedicating it to "Landscape of the Seine with Clouds, for my beloved fiancé at Christmas 1902, Paris, December 1902, by C.G. Jung," was a gift to Emma Rauschenbach, whom he would marry in 1903 (Figure 1).

The other painting bears two dedications. The first reads, "To my beloved mother, for Christmas 1901 and her birthday in 1902." Jung later gave the painting to his daughter, Marianne Neef, co-editor of the Swiss edition of his collected works. The following inscription indicates this. "With gratitude, from my father, to my beloved daughter Marianne. Painting by C.G. Jung, Christmas 1955." In other words, after his mother Emilie's death in 1923, the painting had been preserved as a memento, and 32 years later—54 years after it was painted—Jung presented it to his daughter (Figure 2).

(図1) (図2)

Jung likely loved these paintings, but this also hints at how much his family cherished them. Perhaps passing on paintings within the family was a tradition in the Jung family. As we'll discuss later, a landscape painting of Basel that had been in the parsonage where Jung's parents lived during his childhood was passed down to his son and hung in the house around 1957-58, when Jung and Jaffe began writing his Autobiography.

The fact that aesthetic tastes from decades ago, or even over a century ago, continue to live on intact in modern life may suggest something more than the mere inheritance of family possessions. At the very least, for many Japanese families burned by the backfire of the Pacific War (Greater East Asia War), the thought of passing on an amateur artist's paintings would have been unthinkable. And in the social climate that followed, known as "prosperity," the interior of their homes was unknowingly overrun by the rapidly changing tastes of the times, in pursuit of novelty.

The Jung family tradition likely shares with the traditions of the middle and upper classes of Basel and Zurich, Switzerland, to which Jung belonged. This likely nurtured Jung's aesthetic sensibility and is reflected in the two landscape paintings he painted.

In addition to this painting, Jung painted numerous mandalas and figures of wise old men since his first unconscious mandala in 1916. His students and those around him tried to evaluate Jung's paintings as art, but Jung himself firmly denied that they were art.

Satoko Akiyama speculates that this was because, "Of course, he wanted to make a clear distinction between art and science, but I think it was also out of reserve, stemming from his own perceived weakness for artworks." [1]

In "On the Relationship between Analytical Psychology and Literary Works," Jung emphasized, "What can be the subject of psychology is only that part of a work of art that belongs to the process by which the artist creates it, not the essential part that makes it a work of art. This second part belongs to the question of what a work of art is in the first place, and to that extent it can only be the subject of aesthetic and artistic consideration, but not of psychology. [2]" This attitude corresponds to his own denial of evaluating his paintings as art.

In this article, I will take a look at Jung's two landscape paintings from an artistic standpoint, even though this was probably not Jung's intention. I will not be discussing his mandalas, which Jung considered particularly important as subjects for psychological consideration.

Let's take a look at the paintings.

Jung did not paint these two landscapes from his imagination; rather, it is thought that most, if not all, of them were based on real scenes or were referenced in some way. When comparing these landscapes with the mandalas or The Sage Old Man, one immediately notices the difference in the accuracy of the drawing of objects, including the spatial relationships between them. There is a difference in the impact of objects when sketching from life and when drawing from imagination. It would take considerable professional training to bring imagination to the level of sketching. That said, not all landscape paintings are necessarily sketches. In fact, it is likely that many of the completed works were created in a studio based on sketches.

[Cloudy Seine] - Light shines through the dark cloud-covered sky like a faint sun, and while it's not exactly pleasant, the brightness of the sky is reflected on the surface of the river, so calm it's hard to believe it's flowing. The Seine and its small village are much more modest than the one that cuts through Paris. This side of the river is likely to be fields or pastures. But what was the topography of where Jung was? The horizon, a little too low, obscures this.

His gaze is directed more towards the sky than the ground. Clearly distracted by the dramatic sight of the clouds and light, he seems to have neglected to pay attention to the aesthetic aspects of the scenery on the ground. The construction of a "guiding line" to lead the viewer's gaze from the foreground to the background has been completely abandoned. Rather, like a fence blocking the viewer's journey above ground, stand three pillars that appear to be a church bell tower and chimney, all at the same height. This structure may help identify the small village. However, the distance between one chimney and the bell tower, and the distance between the other two chimneys are exactly the same, which makes it seem like they might represent some kind of symbolism. These are one of the few vertical lines seen in the painting.

Apart from the arabesques of various lines that form the clouds, the only compositional character of this painting are the parallel lines that run across the canvas. In a classical landscape, these parallel lines would have been rhythmic layers of overlapping colors and light and dark, guiding the viewer toward the distance. Here, however, they are simply monotonous stripes.

Jan van Goyen (1596-1656), who is said to have made a significant contribution to the pictorial development of 17th-century Dutch landscape painting, created a work titled "View of Overschie." There are many variants of this painting, which suggest Jan's fondness for the view of the town of Overschie. Let's take a look at a version in the National Gallery in Prague that features landscape elements similar to those in Jung's work (Figure 3). Comparing it to Jung's pictorial structure makes it easy to see how Jan puts together his paintings.

The riverbank, set less than a quarter of the screen, is parallel to the bottom, just like Jung's paintings. However, the pictorial space of this work deepens as you move to the right. The parallel lines of the riverbank actually beautifully change to the horizontal line of the river on the right side. The artist's skillful use of color and light and shade reveals that he is probably standing on a small boat, observing the scene from mid-river. The right bank is not in the foreground of the picture. This gives the pictorial space, which at first glance appears simple, a sudden sense of depth.

The center of the painting is the church spire and the illuminated dock on the riverbank a little to the left. Within the triangle connecting the top of the spire and the two ends of the parallel lines, the vertical lines of the spire, sails, and trees are repeated at various heights, following the principles of perspective, giving the picture a sense of lightness. Trees, buildings, and villagers busy with their daily routines—three on the far left, three at the dock, and one in a rowboat about to depart—are reflected on the river's surface. The artist meticulously captures these flickering and subtle light effects in detail, creating a strong contrast with the lightly and almost supplementary painting of the distant landscape. This creates a sense of tension and gives the painting its distinctive character.

(図3)

Next, we will look at two works by Courbet. He died in exile in Switzerland in 1877, the year Jung was two years old.

This work, "Tornado" (1867) (Figure 4), also boldly lowers the horizon, expressing with overwhelming force the drama of the vast sea and sky ravaged by a tornado. The ferocious appearance of nature seems to resonate with the artist's own intense passion. On the right side of the painting, there is a figure with her back to the viewer standing on a rock, arms outstretched and shouting out into the ocean. She may be a fisherman's wife. However, this figure has a much more significant meaning than the figures often depicted as scattered objects in natural scenery in classical landscapes. For this reason, one could say that the work retains traces of Romanticism.

However, ten years before this painting, Courbet also painted a small piece, "The Lagoon of Palavas," now housed at the Musée Fabre in Montpellier (Figure 5).

I have chosen as examples works whose landscapes and apparent compositions are as similar as possible to Jung's painting, but please also pay attention to the period in which the work was created. "The Lagoon of Palavas" is known to be a sketch. In this work, Courbet stood in the midst of nature, 20 years before the Impressionists, reacting quickly and sensitively to each of its elements, attempting to capture the brilliance of the June sky and the particles of light permeating the air. Technically, he deftly wields a small palette knife to create delicate, solid patches of color.

(図4) (図5)

Through his work, we can see the artist's quiet struggle to navigate the constantly changing trends of art, whether he's ahead of his time or unable to shed his old clothes. This is not evident in the work of Jung, an amateur painter. Of course, there's no trace of embodied technical feats.

When Jung painted "Landscape over the Seine with Clouds," was he internally identified with the celestial drama? He must have been seized by a mystical sensation. The small church may have reminded him of the parsonage where he lived as a child. The church and the shining white Seine against the dark colors no doubt reinforced Jung's mystical sensation. But the earth was merely a backdrop to the celestial drama. People have hidden indoors as if in eternal rest, and the landscape above has become rigid. Unlike Jan van Goyen's village, this village is devoid of the warmth of human breath and voices. The surface of the Seine is as still as a mirror. Jung's mind has erected a fence within the painting, refusing to allow his gaze, and even the gaze of the viewer, to follow the ground into the distance. With a mixture of despair and hope, anxiety and relief, and an indecisive, prayerful feeling, I continue to gaze up at the sky along with Jung.

The same can be said of the other painting, a sunset scene, where the viewer's gaze does not reach the depths of the screen.

The lines that make up this painting are more complex than the former: the gentle curves of the low mountain ranges, the vertical lines of the trees, the meandering lines of the river. But our gaze inevitably stops just short of the screen.

Why?

This is because the most beautiful part of the painting, with the faint light of twilight reflected on the river's surface, is in the foreground, while the rest of the painting is treated as a relatively flat bluish-gray surface. The four trees to the left of the silhouetted pine tree stand like a fence in the center of the picture, as in the previous painting, blocking the viewer's viewer's gaze from progressing further into the picture. If one follows the river from the foreground, relying on the light of the current -- and indeed, the river flows down in front of the picture -- as soon as one passes the trees, the river turns to the right and is carried away from the picture plane. Conversely, if one were to re-enter the painting from the point where one has just been thrown out, the current would carry one's gaze down to the bottom of the picture plane. The viewer's gaze continues to circle around the roots of the five trees.

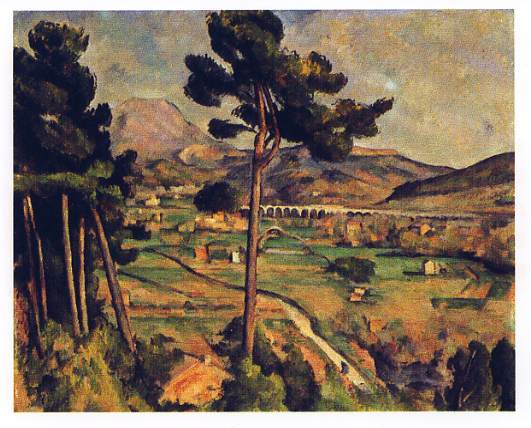

Let's take a look at Cézanne's Mont Sainte-Victoire (1885-87, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Figure 6).

A pine tree is depicted in the center. Its top extends beyond the canvas, much like the pine in Jung's painting. It is this pine tree that the viewer's eye is first drawn to. But then, the gaze shifts to the pale pink Mont Sainte-Victoire towering in the distance. This gaze is never impeded; it is guided by its own will.

Why? A village road meanders gently around the foot of the central pine-covered hill toward Mont Sainte-Victoire. Where the road disappears into the green fields, a white bridge stretches horizontally across the canvas, piercing the vertical trunks of the pine trees. Both the road and the bridge are striking. This is because white is used in only two places in the painting: the road and the bridge. The viewer's eye, entering from the right side of the canvas, follows the bridge and enters behind the central pine. Then (psychologically) our gaze collides with that of someone following the village road from below. Why does the gaze move from below to the distance? Before the bottom of the village road leaves the picture plane, it is blocked by the green of the foot of the hill, and as if to reinforce this, what appears to be a small figure seen from behind has been painted in two layers of black and gray. What a magnificent drawing!

But here, before the gaze that collided with it earlier can even leave the picture plane, it is blocked by a large black mass of five pine trees, which almost completely block the left side of the picture plane. Directly above the intersection of the two lines is Mont Sainte-Victoire. Moreover, the black of the pine trees and the pale pink of the mountainside create a beautiful contrast. The contrast of colors is exquisite. Once our gaze reaches this point, there is no doubt that the center of the painting is there. We take a deep breath of the bright light and green breeze of southern France that fills the vast perspective.

(図6)

Just as Jan van Goyen was fond of the view of the town of Overschie, Cézanne continued to confront Mont Sainte-Victoire throughout his life. Looking at the variants of Jan van Goyen's works, one notices slight variations in the exterior appearances of churches and buildings. He wasn't necessarily depicting them accurately, but rather following the demands of pictorial form. Cézanne was no different. He skillfully deconstructed and reconstructed natural scenes to uncover the artistic secrets of landscape painting.

So far, I've pointed out the sense of obstruction felt in Jung's landscape paintings, and examined one of the causes as a problem with composition. However, even if we excuse them as amateur works, there's no denying that they have a certain charm. I should also draw attention to one technique in the use of space. While it's difficult to discern this in the illustration, there's a subtle lightening of the sides of the solid black trunks of the pine and other trees, as well as the small bush on the left. Using a delicate kind of blurring technique, Jung attempts to express backlighting while at the same time making the space between the subject and the background more sensual. This technique can also be seen, albeit more extreme, in the works of Salvador Dali.

However, perhaps the greatest characteristic of Jung's landscape paintings is a certain "mood."

"The night slowly ascends to land, / Leaning serenely on the mountain's mysterious branches, / His eyes watch as the golden scales of time / Stand still, balancing their plates. / The spring raises its voice above all else, / Singing into Mother Night's ears, / Of this day, of the days that were.

The lullaby of ages past, / The night is tired and refuses to listen. / The blue of the sky, the balance of the passing time / Is good for the night. / But the spring still clings, / Sleeping, its waters still sing / Of this day, of the days that were."[3]"

The poem by German Romantic poet Eduard Mörike (1804-1875) seems to capture the mood of Jung's painting.

We know that Jung's two works were gifts to his fiancée and his mother. But the feeling we get from these works is not one of cheerful joy or merriment. Dominated by the pale, vague light of dawn and twilight, the mood is solemn yet slightly melancholic. Where everything is subdued in a blue-gray hue, the flowing river, reflected in a mercury glow, seems more like the quiet murmur of an elderly person than a symbol of the beginning of a youthful life.

No one is to be seen anywhere. Not even a glimpse of the work left to be done today for tomorrow can be seen. Nature has lost its powerful sense of volume, revealing the silhouette of a "mood." What we see there is neither the true appearance nor a likeness of nature. It is nothing other than a reflection of Jung's own loneliness, standing outside the picture plane. As if peering into his own inner world, he views the landscape with his mind's eye.

"Close your physical eyes in order to see first with the eyes of your mind. Then bring to light what you have seen in the dark, so that it may in turn affect others from without to within."[4]"

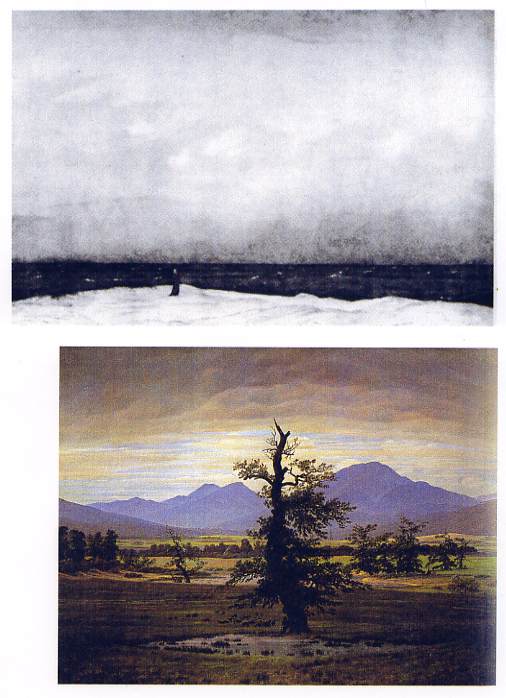

These are the words of the German Romantic landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840). He made this the fundamental principle of his landscape paintings. Yes, landscape paintings!

There is no trace of his creative approach, striving to capture an image of nature. He would shut himself up in his studio, darkened by the sunlight, and immerse himself in his work. Of course, creating landscapes!

His only pleasure was taking walks alone in the faint light. His daily routine was to take the first walk when the sky was beginning to lighten and the light was still fading, and then a second walk at dusk or sunset, when the lingering light was still shining.

When I look at Jung's paintings, my mind begins to overlap with that of Friedrich the solitary walker. Tracing their lives, as if to connect their temperaments, I come across incidents from their childhoods that involved "water" and "the dead."

Friedrich's incident occurred when he was 13 years old.

He was ice skating with his younger brother Christoph when the ice broke and Friedrich fell into the water. His brother tried to save him, but instead, Friedrich drowned right before his eyes.

Friedrich's contemporaries apparently thought that this incident was the cause of his melancholic personality. His melancholy and aversion to people remained constant throughout his life. Those who knew him never even considered that he would ever decide to get married.

At the same time, however, he seemed driven by a desire to explore, leaping into the ruggedness of nature, climbing cliffs, and observing, like someone willingly digging his own grave.

The figures in Friedrich's landscape paintings are always shown from behind. They gaze into the distance, as if expecting something or having given up.

Jung's Autobiography tells of a memory from when he was about three years old, when his mother took him on a short trip to Lake Constance. The young Jung was completely captivated by the lake.

"The waves from the steamship crashed against the shore, the sun sparkled on the water, and the sand at the bottom swelled with the waves. This expanse of water seemed to me incredibly pleasant, indescribably beautiful. From that moment on, the idea of living near a lake took hold of me. I realized that no human being could survive without water.[5]"

...However, after sharing this memory, another memory immediately came to mind. This contrast not only shocks the reader, but also suggests the depth of the shadows in Jung's mind.

...fishermen brought the drowned body to Jung's father's parsonage. Jung wanted to see the body immediately, and despite being forbidden to do so, he wandered around the laundry shed where it had been placed.

"Finally I came across blood and water trickling into the open sewer along the slope behind the house. I found this extraordinarily amusing."[6]"

This was before he was four years old. Later, a little older, he actually saw a corpse.

It was during a great flood. After the waters subsided, he heard that several bodies had been found buried in the sand. Jung again, desperate to get something going, went to take a look. He eventually found the body of a middle-aged man in a black frock coat.

Young Jung then fascinatedly watched a pig being slaughtered. "My mother taught me it was a very horrible thing, but butchery and dead people simply amused me. [7]"

Jung's interest in corpses cannot be simply explained as the intense curiosity of childhood.

Then came 1909, when his conflict with Freud was finally coming to the surface.

Jung and Freud were traveling together to the United States, and the two met in Bremen. During their stay there, Jung remembered the "peat bogs" that were occasionally discovered in the area. These were prehistoric humans who had drowned or been buried in the bogs, and then, in the process of mummification, had been crushed flat by the pressure of the peat, only to be unexpectedly dug up in modern times.

Jung's interest irritated Freud, and Freud repeatedly asked Jung, "Why are you so interested in these corpses?" Eventually, Freud told Jung that he was convinced that Jung had a death wish for him. Naturally, Jung was surprised by this interpretation.

In The Underground, Colin Wilson states that Freud's interpretation was likely correct.

In Jung's Autobiography, edited by Jaffe, the episodes are not arranged simply chronologically, but rather one memory brings up another. Since Jung is said to have written down his childhood stories himself, the order seems to have been chosen as Jung's thoughts dictated.

What caught my attention was Jung's first memory of art, which follows his memories of slaughter and corpses.

It was an "Italian-style painting of David and Goliath." The painting likely depicted David decapitating the giant Goliath and standing proudly next to the corpse, his blood-stained broadsword hanging from his neck.

"I don't really know how it ended up in my house," Jung says. It was a bloody painting that had no place in the home of a Protestant pastor.

The one in Jung's house was a copy, but Jung says the original is in the Louvre, so it's possible that he encountered the painting again for the first time in 20 years during his stay in Paris in 1902.

Come to think of it, Richard Müller, who organized the "Degenerate Art Exhibition" in Dresden, where Nazism was raging, was a year older than Jung and was himself a painter. The work is extremely gruesome, as if it exposed the sadomasochism of Nazism to the light of day. I suddenly remembered that he painted "David and Goliath" in 1906.

Jung does not write about what the young Jung felt when he saw "David and Goliath." However, I believe that the feeling of having seen something naughty is evident between the lines. This association catches my attention especially after he says, "Slaughter and dead people merely amused me."

To put it bluntly, Jung may have been alluding to his own sadistic tendencies while recounting his childhood memories of corpses. I am also intrigued by the following description.

It is spoken of as if purifying his inner world. This is Jung's first mention of a painting that he considered beautiful. It is likely that his sensitivity to painting was cultivated based on that painting.

"There was another old painting in that room that now hangs in his son's house: a landscape of Basel dated to the early 19th century. I would often sneak into this dark, unused room and sit in front of the painting for hours, admiring its beauty. It was the only beautiful thing I knew. [9]"

This painting is the Basel landscape mentioned at the beginning of this article, inherited by Jung's son. It reveals Jung's image as a father, intent on passing on the most beautiful thing to his son. In other words, Jung's memories of purity and impurity, mediated through water, ultimately reached a moment of bliss, as if redeemed by beauty. Perhaps we can think of this memory as being entrusted to his son and passed on through a single painting.

Gaston Bachelard wrote in *Water and Dreams*, "The dualism of pure and impure water is far from balanced. Of course, the moral scales tip toward purity and good. Water leads to goodness."[10]" He also quotes Paul Claudel, writing, "Everything the heart desires can always be reduced to the image of water."

Let's return to Jung's landscape paintings and attempt a final comparison with Friedrich's work. We can already sense that the water that appears in both of Jung's works must have a deep connection to his distant memories and his inner world. The Seine that Jung painted is the Seine and yet not the Seine. Even in his sketches, he transcends materialism, just as Friedrich's theory of landscape painting suggests.

What about the poignancy of Friedrich's 1808 work, "A Monk by the Sea" (Fig. 7)? The monk's figure seems about to disappear before the vast sky and sea. This is Friedrich's mental state as he confronts death. The space converges in his mind with great tension.

The motif of "Lonely Tree" (1823, Fig. 8) is very similar to Jung's painting. A huge tree stands on the shore of a swamp, and at its base, a shepherd leans his shoulder against it, facing backward. The sun is beginning to rise. But this side seems still to be in the realm of night. The marsh water is tinted crimson, reflecting the morning sun, but Jung has not yet fully awakened from his deep slumber.

In fact, 17 years earlier, Jung had featured this giant tree in his work "Giants' Tomb by the Sea." It is one of three giant trees standing near the burial mound.

To me, this tree represents Friedrich himself, and the shepherd his brother Christoph.

(図7) (図8)

In Friedrich's landscapes, people commune with all things while agonizing over their own separation from others. Just as Friedrich sensed a secret principle corresponding to mental activity in the vastness of nature, perhaps Jung also sensed the inner transformation of the landscape.

In early 1944, Jung lost consciousness due to a combination of a myocardial infarction and a broken bone, and in his delirium, he experienced a variety of majestic visions. Quoting a line from Faust, he described this state as floating "in the image of the universe."

This feeling is none other than the bond between Jung and Caspar David Friedrich. It expresses the same spiritually elevated view of nature that so uniquely defined German Romantic landscape painting. Jung sensed and expressed this early on when he painted two landscapes in 1902. Indeed, he must have already been familiar with it when he crept into the dark rooms of the rectory and immersed himself in the delights of gazing at the landscapes of Basel. At this point, Jung's aesthetic sensibility had reverted to the tastes of his grandfather's time. It seems to me that Jung maintained this somewhat outdated taste throughout his life. The 85 years that Jung lived were a time of rapid change in artistic thought and modes of expression, and no artist could rest content with the styles of the past. However, Jung did not venture into modern art, publishing only two essays, "Ulysses" and "On Picasso," in 1932. Regarding the dotted line connecting Romanticism, Jung, and Surrealism, he honestly confessed that "this is something I cannot understand."[11]" and that was the end of it.

Satoko Akiyama points out, "Jung's lack of exposure to contemporary art may be due to his inherently conservative and introverted nature. The Swiss, raised in mountainous regions, are generally conservative, but Jung and the Jungians around him were particularly known for their conservative tendencies, being part of the middle and upper classes in Zurich. (Omitted) Many of them were introverted intuitives, and seemed to have difficulty with things that required a certain degree of sensory function, such as painting.[12]"

It seems I too have reached this point through Jung's landscape paintings.

Time passed leisurely around the paintings hanging on the walls of Jung's home.

References

[1] Satoko Akiyama, "Jung and Contemporary Art," Gendai Shicho, Vol. 7, No. 5, Seidosha, 1979.

[2] Jung, "On the Relationship between Analytical Psychology and Literary Works," translated by Yoshitaka Takahashi, Nihon Kyobunsha, 1970.

[3] Mörike, "At Midnight," translated by Kawamura Jiro, German Romantic Poetry, Kokusho Kankokai, 1992.

[4] Einem, "A History of Modern German Painting," translated by Kanbayashi and Muto, Iwasaki Bijutsusha, 1985.

[5] [6] [7] [8] [9] Jaffe (ed.), Jung's Autobiography, translated by Kawai, Fujinawa, and Idei, Misuzu Shobo, 1972.

[10] Bachelard, "Water and Dreams," translated by Obama and Sakuragi, Kokubunsha, 1969.

[11] Jung, "Ulysses," translated by Eno Senjiro, Nihon Kyobunsha, 1970.

[12] Same as [1].

First published in the Autumn 1993 issue of AZ, published by Shinjinbutsu Oraisha co., Inc..

コメント

コメントを投稿